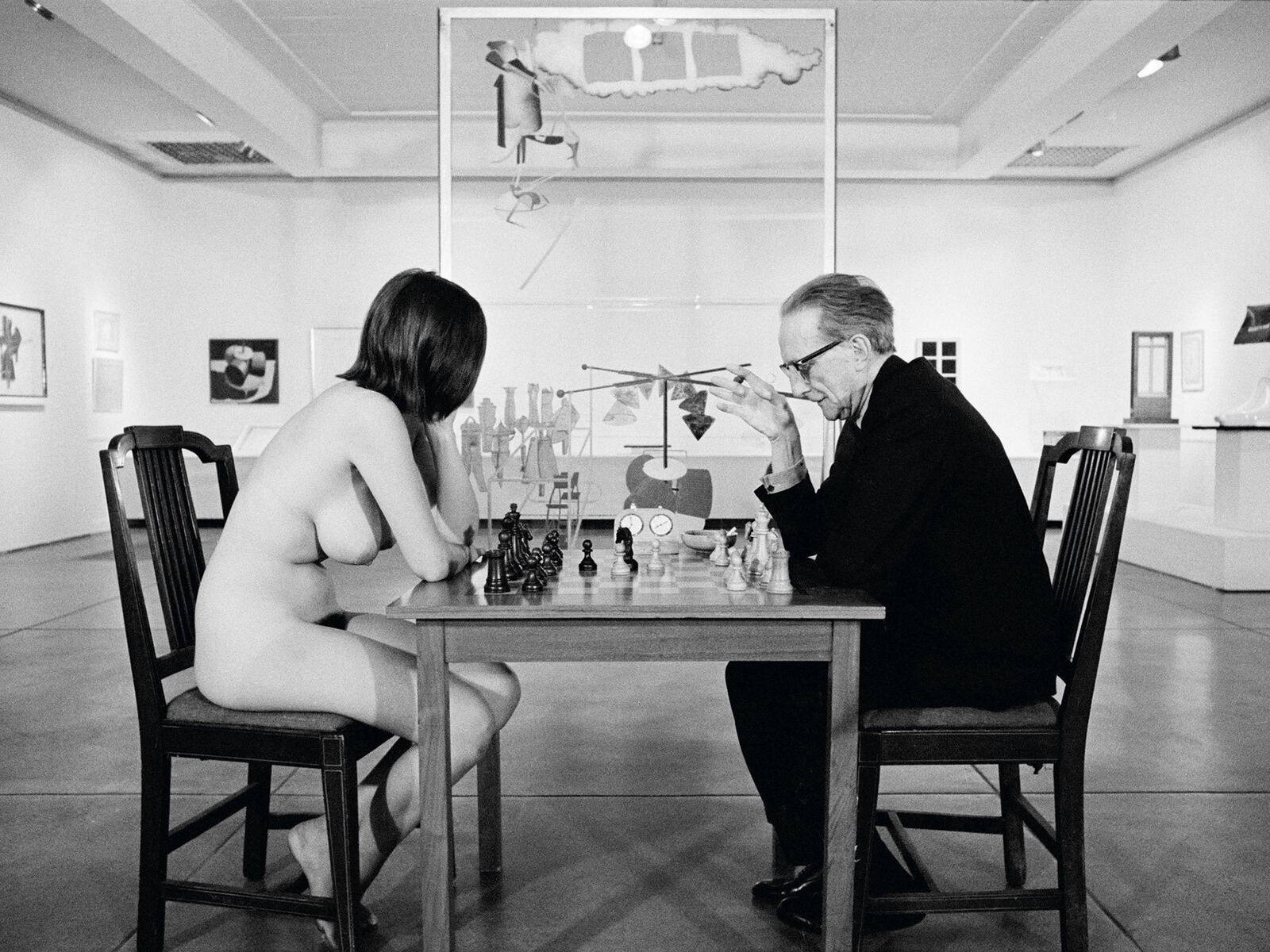

Photo: Julian Wasser, "Duchamp Playing Chess with a Nude (Eve Babitz), Duchamp Retrospective, Pasadena Art Museum, 1963"

Photo: Julian Wasser, "Duchamp Playing Chess with a Nude (Eve Babitz), Duchamp Retrospective, Pasadena Art Museum, 1963"

How One Exhibition Legitimized an Entire Art Scene

I just watched “Duchamp Comes to Pasadena” and this story resonates differently when you’ve spent two decades in production.

Here’s the setup. In 1963, LA’s art scene was basically nonexistent. The County Museum featured stuffed animals and Egyptian artifacts. The city was a cultural backwater. Nobody took it seriously.

Then Walter Hopps pulled off something remarkable. He brought Marcel Duchamp’s first American retrospective to the Pasadena Art Museum. Not to New York. Not to Paris. To Pasadena.

Before Pasadena, Hopps had founded the Ferus Gallery in 1957, the first major contemporary gallery in LA. He’d already been showing Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Craig Kaufman, Ken Price, Ed Ruscha, and Larry Bell. The artists who would define the LA look. When he moved to the Pasadena Art Museum as curator, he was still in his twenties. And he decided to mount a retrospective of over 100 works by an artist who had been out of the public eye for decades.

The artists who saw that exhibition had literally never encountered this work before. There were no accessible publications about Duchamp. His pieces weren’t in museums they could visit. Some knew the name, but they didn’t know his work or understand his significance.

Suddenly there was this entire body of work: ready-mades, found objects, conceptual art, just sitting there in Pasadena for them to discover.

The Moment Becomes Folklore

If you need proof of how legendary this exhibition became, look at the photograph at the top of this post.

That’s 20-year-old Eve Babitz, naked, playing chess with Marcel Duchamp in the museum gallery. The backstory is perfect LA.

Babitz was already embedded in the scene. Daughter of a violinist and an artist, goddaughter of Igor Stravinsky, she partied with Bengston, Kienholz, Price, Larry Bell, and Robert Irwin. She was dating Walter Hopps. When she didn’t get invited to the opening party (Hopps’s wife was in town), she plotted revenge.

Photographer Julian Wasser suggested she play chess with Duchamp. Naked. In the gallery. Before the museum opened for the day.

Babitz told the Archives of American Art it seemed “like the best idea I’d ever heard in my life. Not only was it vengeance, it was art.”

They didn’t tell the museum or Duchamp beforehand. During the game, while teamsters moved artwork around them, Babitz and Duchamp discussed Stravinsky and The Firebird. Duchamp won. Wasser got his shots. When Hopps walked into the gallery, his Double Mint gum fell out of his mouth.

The photo became iconic. Part of the mythology. That’s what this moment was like.

What Actually Happened

The artists didn’t try to copy Duchamp. They took something else: permission. The idea that art could be something entirely different. One artist described it perfectly: “It was like the first time we put suits on.” They grew into their image as serious artists doing meaningful work.

Within two years, the LA County Museum of Art opened. Galleries flourished on La Cienega Boulevard. The entire LA look (Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Craig Kaufman, Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell) all traces back to this moment.

Here’s what’s relevant for anyone building creative communities today.

Legitimacy doesn’t come from consensus. It comes from someone with vision making a bold move. Hopps was a chain-smoking curator in his twenties who “could see into the future” according to the artists. He didn’t ask permission. He just made it happen.

Access changes everything. These artists couldn’t see Duchamp’s work anywhere else. One exhibition gave them the conceptual framework they needed. Sometimes the biggest barrier isn’t talent or drive. It’s not knowing what’s possible.

Small scenes matter. The community was tiny. Ten people at gallery openings. Everyone knew everyone. Babitz partied with the artists, dated the curator, and played naked chess with Duchamp. That intimacy, that tight community? It wasn’t a limitation. It was the feature that allowed them to build something new.

Geography matters less than you think. Everyone said LA was a backwater. The work was happening anyway. If you’re building something outside the traditional centers, that’s actually an advantage. No one is telling you no. No one is enforcing the old rules.

One exhibition. One moment. It became folklore in LA. Artists carried pieces of it with them for the rest of their lives.

That’s how legitimacy actually works. Not through institutions gradually bestowing credibility. Through someone seeing the future and making it happen.

The VFX industry has had its own versions of this moment. Digital Domain launching. ILM pushing practical effects into digital. Weta changing what was possible with performance capture.

Every creative community has these inflection points. The question is whether you’re paying attention when they happen, or better yet, whether you’re the one making them happen.